If a former Prime Minister of New Zealand is involved in a case then you know it is going to attract interest. Dame Jenny Shipley was the Chair of the Board of Mainzeal and it was found that the directors had breached their duties – what happened, and most important, what can we learn from this?

As a director of a company you must act honestly, in the best interests of the company, and with reasonable care at all times. You must not act or agree to the company acting in a manner that is likely to breach the Companies Act 1993, other legislation or your company’s constitution. The outcome of the Mainzeal case comes as a timely reminder to company directors of their duties and obligations.

Founded in 1968, Mainzeal was one of the leading construction companies in New Zealand, responsible for projects such as the ASB Sports Centre in Wellington and Spark Arena in Auckland, just to name a few. However, the construction industry was sent into shock when Mainzeal collapsed and was placed into liquidation in February 2013. Unbeknown to many, Mainzeal had been struggling financially for a number of years. So much so, that Mainzeal’s liquidators brought proceedings against the former Mainzeal directors, claiming they had breached their duties under section 135 of the Companies Act 1993.

What Happened?

The details are summarised at the start of the case: “In 1995, an investment consortium with a focus on investments in China acquired a majority shareholding in Mainzeal’s then holding company. This investment consortium was associated with the first defendant, Mr Richard Yan. The company group came to be known as the Richina Pacific group. In 2004, the group established a new independent board for Mainzeal with the third defendant, Rt Hon Dame Jennifer Shipley, as Chairperson. It operated for nearly 10 years under this board until the company collapsed in February 2013. Its collapse left a deficiency on liquidation to unsecured creditors of approximately $110 million. The unpaid creditors were sub-contractors ($45.4 million), construction contract claimants ($43.8 million), employees not covered by statutory preferences ($12 million), and other general creditors ($9.5 million). Mainzeal’s secured creditor, BNZ, was fully paid out.”

Were the directors reckless?

The crux of the claim came under section 135 of the Companies Act . This section specifies that a director of a company must not—

- agree to the business of the company being carried on in a manner likely to create a substantial risk of serious loss to the company’s creditors; or

- cause or allow the business of the company to be carried on in a manner likely to create a substantial risk of serious loss to the company’s creditors.

Ultimately, the court had to consider if Mainzeal’s directors had been reckless in continuing to trade while Mainzeal’s balance sheet was in deficit, thus placing the company’s creditors at a substantial risk of serious loss?

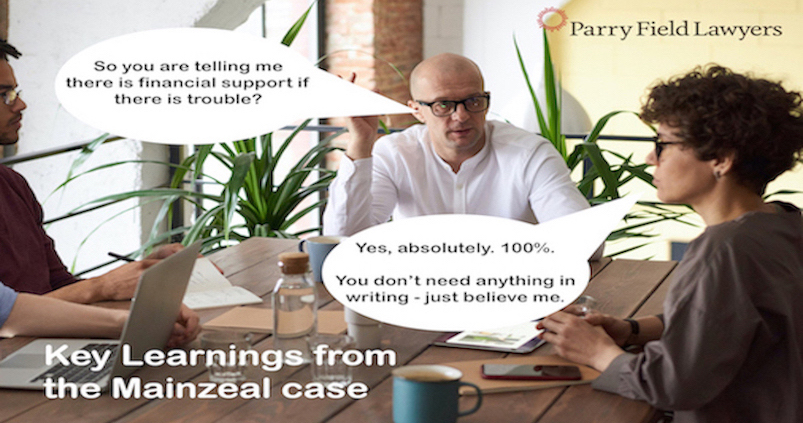

Mainzeal had been trading as insolvent from as early as 2005, when Richina Pacific group extracted considerable funds from Mainzeal by the way of loans for investment in China. However, Mainzeal continued to operate as a going concern, as Richina Pacific provided letters of support for when Mainzeal’s accounts were audited. The directors were also given assurances by email and in meetings that support would be provided by the parent group if it was needed. These representations of financial support were relied on by the directors – but they should have done more. It is important to note that the promise to provide financial support when necessary was never formalised or legally binding (eg loan agreements or guarantees).

The ability for Richina Pacific to provide financial assistance when needed was also limited due to stringent foreign exchange controls exercised by the Chinese governmental authorities. Therefore, this made it extremely difficult to take money back out in China, once it had been taken from Mainzeal.

Mainzeal continued to trade, largely relying on funds that were owed to sub-contractors. It must have been a difficult balancing act to work out how long to continue trading in those difficult circumstances. Ultimately, Mainzeal was unable to pay its debts and was placed into liquidation on 28 February 2013.

Looking at the case there are some fascinating exchanges by email between the Directors and representatives of the parent company. For example, Dame Jenny Shipley wrote:

“While I note your desire to run a central treasury function for the NZ interests it is unreasonable to ask Mainzeal Directors to approve the associated related party transfers without the clear understanding if we are liable for these decisions and the associated obligation or of other persons or Directors are legally responsible. We are not informed as to the purpose of these transfers and would not need to be so if we had a clear indication from those responsible for the group that the request had been approved…”

So the directors were asking some questions – which is always good. But they relied too much on answers like this one that came in reply to these comments above:

“Again, there are no independence issues here as it is ultimately the shareholders who are on the hook for everything. Mainzeal is no in way compromised and Richina has always supported it to the full extent even during its more dire situations…”

Another experienced director, Sir Paul Collins, wrote: “I would have to say I’m at my wits end. I joined the board under the impression Mainzeal was solvent … I accepted all your representations re support and more recently redomiciling in NZ later this year and taking out the BNZ. As you will well appreciate I have dealt with a lot of bad news stories over the years and have found that matters can be worked through when you have all the cards on the table. I don’t have that confidence here. …”

What should the directors have been doing? Asking questions – like they did. What they failed to do was getting the answers documented in binding legal agreements.

The court found that the directors had breached their duties under section 135:

“Whilst all the factors I address below are relevant, there are three key considerations that cumulatively lead me to conclude the duties in s 135 were breached:

- Mainzeal was trading while balance sheet insolvent because the intercompany debt was not in reality recoverable.

(b) There was no assurance of group support on which the directors could reasonably rely if adverse circumstances arose.

- Mainzeal’s financial trading performance was generally poor and prone to significant one-off loses, which meant it had to rely on a strong capital base or equivalent backing to avoid collapse.”

It was held that those were the three key elements in establishing that there had been a breach by the directors. The Court then went on to confirm:

“The policy of trading while insolvent is the source of the directors’ breach of duties, however, such a policy would not have been fatal if Mainzeal had either a strong financial trading position or reliable group support. It had neither.”

As the directors had been found in breach of section 135, the court awarded $36 million in damages. A large sum of money for anyone. The Court found that three directors, Dame Jenny Shipley, Mr Peter Gomm and Mr Clive Tilby had acted honestly and in good faith, therefore each were held liable for up to $6 million jointly with Mr Yan.

This did not go unchallenged. The court left the door open for the parties, if they believed there had been a miscalculation in the amount of damages awarded. Both the liquidators and former directors believed there had been, however both parties had their cases dismissed. An appeal and cross-appeal were filed by the liquidators and former directors.

In 2021 the Court of Appeal found that the directors had breached s 135 of the Act, which exposed the company’s creditors to a substantial risk of serious loss. However, that loss did not materialise and the court therefore no compensation should be payable by the directors.

The court also found the directors had breached s 136 of the Act when they entered into four significant construction contracts. The matter was remitted to the High Court to determine the compensation payable. The former directors are seeking to overturn the decision and the matter is currently before the Supreme Court.

What can we learn: What should the directors have done?

There were a number of red flags for the directors throughout the years. With the benefit of hindsight, there are some important lessons that can be taken from this case:

- It’s really simple, but ask questions. Understand the answers and document them well. If someone says there is support, get it in writing.

- If you are questioning the information you are receiving from others or it makes you feel uncomfortable, seek independent advice from a professional.

- When relying on assurances from others, ensure these are in writing and legally binding.

- Understand your duties as director. Ensure it is clear to whom your legal duties lie with. This is particularly important if your company is part of group of companies.

- If you are facing financial difficulty, continue to review the situation and be extra-vigilant.

- If you have been provided of assurances of financial support, ensure such assurances are clear – ask questions.

Examples of questions could include: How much financial support is available? Are the finances readily available and if not, how long will it take? What are the barriers that need to be overcome? How can we ensure we can legally rely on these assurances?

A recent United Kingdom case of interest

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled for the first time in October 2022 on what triggers the directors’ duty to have regard for creditors’ interests ahead of shareholders interests (that is the company). The case is BTI 2014 LLC v Sequana SA and others.

Conclusion

The final outcome of Mainzeal is outstanding. However, what can be taken away from this case is the importance of the obligations and duties directors have to a company and creditors. The case really emphasised the care that is required, especially if a company is in financial difficulty. It also highlighted, if ever in doubt, seek independent advice, as it is better to be safe than sorry. Also, ask questions and document the answers so there is a clear trail.

This article is not a substitute for legal advice and you should contact your lawyer about your specific situation.

Please feel free to contact Steven Moe at stevenmoe@parryfield.com or Kris Morrison at krismorrison@parryfield.com should you require assistance.