We live in a time when paradigms are colliding. Old conceptions from an extractive economy which have been accepted for decades are being challenged by new ideas that are planted in the soil that dreams of a regenerative economy. One outworking of this is the growth of “Impact Investing”. In this paper we outline what that is, why it matters, discuss examples and cover the implications for NFPs interested in this area.

What is Impact Investing?

Traditionally, the primary driver when looking at an investment has been monetary returns for the investor. “You can offer a 9% return on investment? Well, I can get the 11% over here…” However, such an outlook is limited and narrow because it is only focussed on financial returns.

Impact investing offers a different and more holistic approach. The Global Impact Investing Network provides the following definition: “Impact investments are investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.”

So the alternative presented by impact investing is that there are other considerations that need to be thought about beyond financial returns, such as:

- What does the business actually do – is it an extractive business which is harmful to the planet?

- Who does the buisiness employ – is the business model built on the premise that there is exploitation in how cheaply it can produce whatever it makes, either onshore or offshore?

- What other outcomes are there – perhaps social, cultural, environmental or other factors will be mpacted by the business?

Key attributes

Some of the key attributes of impact investing include a desire to achieve a positive social/environmental (or other) impact, a plan to measure this impact and an expectation of generating a financial return on the capital invested. So in an NFP context, this is more than just grant making (or receiving) as the funds actually come back to the investor. The key is that there will be some positive impact through the investment, while still generating positive return for the investor. This also means an investor may need to think a bit longer before they decide what to invest in.

How does Impact Investing Work?

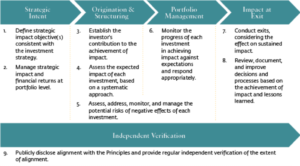

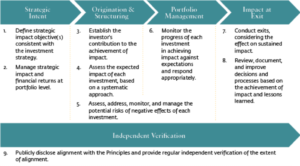

Impact investing is not a one-size-fits-all model. Different investors may have different impact and financial aims, meaning the form and terms and conditions of investment will be different in each scenario. However, to create a level of consistency, the International Finance Corporation has created a framework for managing impact investing.

Source: Investing for Impact: operating Principles for Impact Management, IFC, 2019,

https://www.impactprinciples.org/sites/opim/files/2019- 06/Impact%20Investing_Principles_FINAL_4-25-19_footnote%20change_web.pdf

It is worth noting that there are different types of impact investing (e.g. managed funds, CDFIs (Community Development Finance Institutions), SIFIS (Social Investment Finance Intermediaries), social impact bonds, direct investment, investment clubs and catalytic investment).

Why is Impact Investing Important?

Increasingly, organisations are being pressured by both shareholders and stakeholders to achieve a social impact alongside financial returns. Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock (the largest investor in the world at around US$6.8 Trillion) has stated, “Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.” According to the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing, 85% of investors surveyed were interested in engaging with Impact Investing. It is clear that funders are now expecting more from the organisations they choose to invest in.

A Broader Shift?

This represents an expanded view of the role companies play and to whom they are accountable. While companies have traditionally focused on achieving the best financial outcome for their shareholders, the interests of stakeholders is becoming increasingly relevant. The Companies Act 2006 of the United Kingdom focuses on promoting a company’s success, “for the benefit of its members as a whole.” Impact investing is only one aspect of a much broader shift in thinking that is challenging (and hopefully transforming) the shareholder capitalist order.

Examples of Impact Investing in NZ

It is useful to look at some examples of impact investing to show this is more than just a theoretical discussion.

Ākina

The Ākina Foundation is dedicated to transforming the values of the New Zealand economy by supporting enterprises and businesses in creating positive impact for the land and people of Aotearoa. Ākina is leading the way in Impact Investing, co-establishing New Zealand’s first impact investing fund. The Impact Enterprise Fund manages $8.7 million and has supported several projects, including Waikaitu and Melon Health. Ākina also introduced Impact Investment Readiness Grants to provide social enterprise and impact-driven businesses support to become “investment-ready”.

Purpose Capital Impact Fund

The Purpose Capital Impact Fund has raised $20 million and is aiming to raise $30 million to, “generate meaningful impact and financial returns in its regions and across New Zealand.” Having already reached its initial target, it is one of New Zealand’s largest impact investing fund. The Fund focuses on tackling big issues such as affordable housing, environmental degradation, climate change and inequality and aims to generate financial returns of 5-6% per annum (net of fees and expenses).

Community Finance

Community Finance provides low cost finance to New Zealand’s Community Housing Providers to build new, safe and affordable homes for Kiwis (disclaimer: the author is he chair of this company). Their finance model enables investors, philanthropists and foundations to invest in a meaningful and ethical way to help develop thriving, diverse and inclusive communities. Their lending platform, called the “community-to-community model”, enables investors to ethically invest for the benefit of communities and help make a positive impact. Investors receive regular reports on the direct social impact of their investment as well as a financial return of between 2% pa and 2.50% pa, which is similar to the financial returns on corporate bonds and term deposits. Community Finance has partnered with a range of Community Housing Providers including the Salvation Army, Habitat for Humanity and Community Housing Aotearoa to activate new housing supply where it is most needed. Community Finance also has three pilot projects under way in Auckland, as well as emergency transitional, social and affordable housing projects in Bay of Plenty and Christchurch.

What does this mean for New Zealand NFPs?

By just relying on grants, NFPs are reliant on other activities (such as fundraising) to raise funds.Conversely, the tenets of traditional investment may clash with the charitable purposes of aNFP. Impact investing provides NFPs with a unique way to invest funds in accordance with their charitable purposes (or potentially to receive investment themselves). The trustees of a charitable trust may be able to invest the trust’s assets in projects that are making an impact, while receiving a return.

However, impact investing isn’t for everyone and there are many things that a NFP should consider before engaging with this new model of investing.

Option B: Those seeking to Invest

What do NFPs need to consider when exploring impact investing within their future investment plans?

It is important for NFPs consider what impact they want to achieve – is the way they have always done things the only way? One option that could be considered is through investing for impact. Critical to this is how to measure impact and set expectations and create accountability. The NFP will also need to address what to do if the impact is not achieved.

As with any form of investing, impact investing carries risks which NFPs should consider. For example, as impact investing is an emerging concept, there is less capital in the market. This means that it may be harder to sell investments if capital is needed. NFPs need to think about whether they will be in a position to wait the full duration of the investment. What are the primary motives – purpose or profit or both?

What types of projects suit this model of investment?

There are different types of projects that NFPs may invest in. An organisation may seek seed funding, allowing them to research and develop new ideas. Alternatively, money may be invested to grow an existing project or enable a business to perform a contract (e.g. social bonds). Finally, impact investment can allow an organisation to purchase assets which will provide revenue over time.

What legal questions does an organisation need to take into consideration before embarking on this model?

The governing body of a NFP must ensure their investing activity complies with legislation and their governing documents. For example, Sections 13A and 13B of the Trustee Act 1956 enable trustees to invest prudently in any property. This means that trustees must exercise care, diligence and skill when investing trust assets. Section 13E sets out a list of factors that trustees may consider when choosing to invest. It is important that trustees seek professional advice when choosing to invest and take steps to reduce the risk of breaching their duties.

The trustees must also ensure they are complying with the trust deed. The trust deed may direct trustees how to use the trust’s assets and have instructions on investing. The charitable purposes of a registered charitable trust will also guide the trustees as to the type of projects they should invest in. Where possible, it may be beneficial to amend the trust deed to expressly allow the trustees to carry out impact investing. If the trustees are unsure of their obligations, it is recommended that they obtain advice.

Positives

There are many positive aspects of impact investing. It represents the future of investing, as traditional views of business and charity are being challenged. Impact investing also diversifies income streams, opening up new opportunities to generate income while making a positive impact. And it empowers others through more than just providing grants. While there may always be a place for grants in the NFP sector, impact investing widens the scope of both fundraising and investing and successfully integrates profit with purpose.

Challenges

While impact investing is an exciting and emerging concept, there are several challenges that must be addressed to ensure its growth. Key challenges include:

- Readiness: while there are many opportunities to create impact in New Zealand, some entities are not yet ready to seek investment. Groups that would traditionally seek grants may lack the training to engage with investors. This means that more resources need to be allocated for preparing these organisations for investment.

- Greenwashing: as impact can be hard to measure, there is a fear that organisastions may claim their product/service creates a positive impact but, in reality, has very little social/environmental benefit. This means standards to measure impact must continue to be developed and investors need to have clear reporting mechanisms to ensure accountability

- Inefficiency/difficulty: in a 2016 survey carried out by Ākina, 10% of organisations surveyed had sought impact investment but had found the process difficult and inefficient. They also noted that there was often a disconnect between the objectives of the investor and investee. This means that organisations need to consider how to make impact investing more accessible to organisations and investors need to clearly set out their expectations before investing.

Impact investing is here to stay and we are confident it will grow as more people step back and think through how they are investing their funds. It represents one element of a broader shift in thinking, as the traditional values of investing and capitalism are challenged. While not all organisations will be able to engage in impact investing, NFPs should consider how they can best achieve their desired impact and whether impact investment is the way forward. They should think about what impact they want to achieve, how to measure that impact and how to manage the risks of investment. Finally, they should ensure they comply with any legal obligations imposed on them to prevent a breach of duty. We look forward to see how impact investment reconciles profit with purpose, for the benefit of shareholders, stakeholders and the future of Aotearoa.

Should you need any assistance with these, or with any other NFP matters, please contact Steven Moe at Parry Field Lawyers stevenmoe@parryfield.com (+64 3 348 8480).