In this article I want to tell you some key points that I have learned about setting up an impact driven organisation in Aotearoa New Zealand. This applies whether that ends up with a charitable structure or a for profit structure or some form of hybrid. The reason that I know about this is my job is as a Partner at Parry Field Lawyers where I have a unique practise of law focusing on helping purpose driven people achieve their mission. Also, with more than 200 interviews for seeds (www.theseeds.nz) I have spoken with some of the best entrepreneurs in New Zealand and gained their perspectives.

So to download all this information to you I am going to share here about three things I think are key to know. I would be curious if you agree with me, and it might be that you know others who would appreciate the challenges because I am going to give it to you straight. I commonly go through these points – probably 2 or 3 times a week – with people who are wondering about setting something new up so this is also going to be a lot more efficient as I can get people to listen to it before speaking about the specifics of their situation.

• First, I will discuss the three key questions to ask before considering the detail of what structure is best.

• Second, we will look at three of the most commonly used legal structures for impact driven people.

• Third, some reflections on the way to enshrine impact within those structures and the key things needed.

So let’s turn to the high level questions you need to get right from the beginning. Don’t skip over this part…

Part 1: The Three High Level Questions to ask first

What is your purpose?

The first thing to remember is that the purpose and mission needs to come first. What is it that you really want to do? The detail of what legal vehicle to choose then becomes a secondary consideration that is about how you best fulfil your purpose. I encourage you to clearly articulate your mission and your purpose because that will drive all other decisions. This is the “power of why” and will be what you come back to when things get blurry and you wonder why you started on this journey. Also I want to know what that is in just 30 seconds – not the 5 page version, just the three short bullet point version. If you can reduce it down to that then you will be able to convey it clearly to others as well.

So why is getting the purpose important?

The purpose is the first key consideration. Why? Well I like to think of it like this – if you go buy a car there are many options. You might want to get an off road 4×4, or a convertible, or a 7 seater – there are a range of vehicles that depend on what your purpose is. In the same way when choosing a legal vehicle we need to understand the purpose of what you want to do. Think of a limited liability company as one type of special purpose vehicle, the same with cooperatives, incorporated societies or charitable trusts. So we need to know the direction you want to head in order to decide on the right vehicle.

What fuel is driving the vehicle?

The second key consideration comes from Jerry Maguire and the phrase “Show me the Money!”. Money is like the fuel that is needed for the vehicle to run – whatever type is chosen. There are two parts to this which affect the decision. Where is the money coming from – sales of product or services, private investment by issuing shares, loans, donations or grant funding? And also, where is the money going to – will there be private profits for individuals or will the funds be reinvested back to promote the mission? All of these factors are critical to work out what structure is best.

Replication?

The third question is a bit different. But before we get into the legal structure options I think it is important to ask this: Is there someone out there already doing what you plan to do? We see in New Zealand a lot of replication where people want to do good and assume that to do so a new initiative is needed. I don’t think that is always the case. If the mission and purpose is most important then strip away any ego associated with founding something new and ask the hard question: for the good of the cause am I better to come in as a strong supporter and work with others already doing the mahi? This may sound like a strange thing to be proposing since my job is to act for people setting something up so I am doing myself a disservice by advocating this thinking – instead I could fan the flames of starting something new. But there is a bigger picture here and if I can encourage one person to not start something new and instead come in as a big advocate and supporter of a struggling initiative that just needs some volunteers then that will be better overall. So please do look around and have conversations about collaboration before going off and setting up something new.

Part 2: The three best types of legal structures to consider

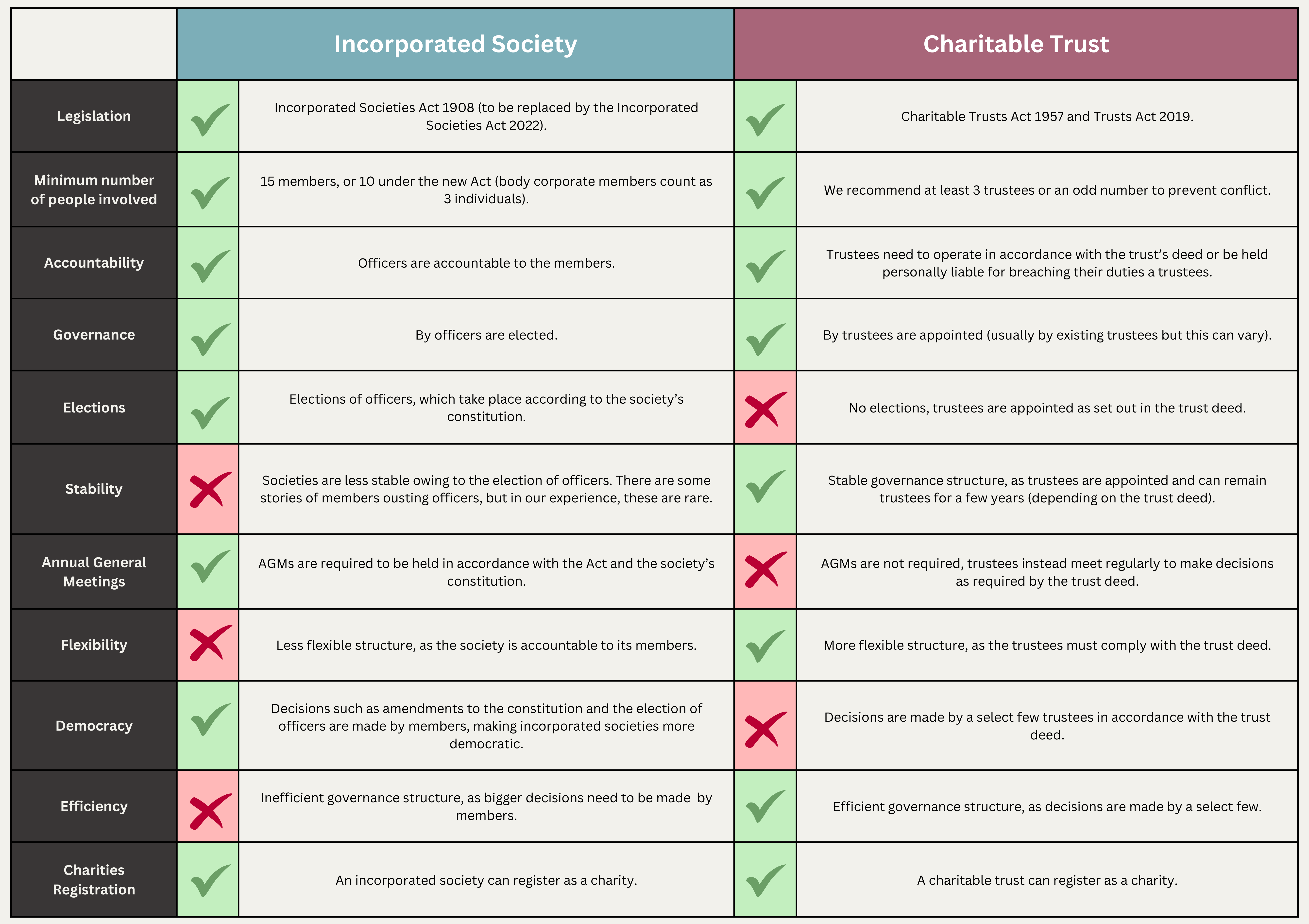

There are many possible structures but I am going focus in on the ones I think are the simplest and easiest ones. There are basically three options. They are:

Set up a Company: This is a commonly understood vehicle for running a new initiative. As a positive you can privately benefit through dividend return to shareholders, you can more easily access investors by issuing them shares, people understand the structure over other options. The key ingredients are a director, a name and a shareholder. The downside is that you will be less likely to get grant funding or donations, people make assumptions that what you do is driven by profit rather than purpose, so there can be a lot of explaining needed, and if taken over the company might lose the essence of why it was originally founded. I am setting up many impact driven companies so am happy to discuss all this in more detail if anyone would like to know more.

Set up a Charity: Setting up a charity provides a nice vehicle because you are forced to write down you purposes – I think that is a good thing. You need to fulfil one of four charitable purposes: Advancing education, reducing poverty, advancing religion or purposes beneficial to the community. So just because what you want to do is “good” doesn’t necessarily mean that it will be charitable. Becoming a charity results in significant tax benefits because you are helping society – for example, you can issue tax deductible receipts to donors. However you will not be able to privately benefit (apart from market rate salaries), will not be able to issue shares that return dividends to shareholders (unless to another charity) and will have difficulty raising capital funding. One common misconception is that a charity must be a Trust – in fact, companies can be charitable as well it is just that they must clearly articulate that there is no private benefit and state what the purposes are. I am setting up several charities each month across the full range – recent examples include an ocean focussed charity, one setting up Buddhist temples, one working with children on design thinking – a very large range.

Hybrid option: Remember the “show me the money” point earlier? Well this is where it kicks in – if funding is coming from private investors, this option is preferred over a charity. Whereas if funding is likely from grants or donations, then the charity option may be preferred. There is no one template that will apply for all. While it involves some duplication of having two entities, sometimes what I see people end up considering is a hybrid option. This involves having a company while also setting up a Foundation which is a charity. How closely aligned they are will depend on the circumstances. If setting up a charity then part of the thing to consider is having independence in that charity so there is no chance of a conflict of interest. Ultimately this is all about finding the best way to have maximum impact. Increasingly I am seeing pull from either end – private companies wanting to give back through creating a charity, while charities are looking to commercialise some aspect of what they do in order to generate another income stream. I think the lines will continue to blur as we increasingly move towards discussions of impact being the most important thing. Like I said at the start it then is down to the detail as to the type of legal structure used as the overarching point is that mission and purpose and impact are being implemented.

Part three: Enshrining impact

I want to finish off with a few thoughts about how we started – a focus on impact. Thinking about each of the structures discussed I would just comment that for a charity you are required to set out the purpose you want to achieve, which I think is a really good thing.

For a company, it is not legally required to set out what your mission is – which I think is an oversight that one day will be corrected – but it is possible to enshrine your impact by setting out your mission in a constitution. That is a public facing document and if I get involved I try to have clients articulate their mission and purpose right at the start so that they are open and clear with the world about what they are there for.

I would encourage you that whatever entity type you end up choosing that you really come back to the mission and purpose and clearly set out what it is. I can guarantee that will be the most valuable point to get straight. Once that is done then it will help you to decide on the detail of which type of entity to choose. You may notice that this summary focusses more on the high level questions than the detail – that is on purpose.

My final thought is to consider how you report on impact – wouldn’t it be great if we all started measuring and talking about impact in ways that get beyond financial metrics. It is really hard to do but research it and get amongst it to lead the way in how you measure and talk about the impact you are having. If you can do that then I am confident your venture will be more assured of success.

I’ve enjoyed reflecting on this topic and would be happy to discuss further with you – and if I directed you here to listen before we have a phone call then I look forward to chatting sometime soon.

Until next time.

Note: This is a short overview of issues – inevitably situations will be different for each context and you need to consider a variety of issues such as Financial Markets Authority rules, Tax considerations, employment, shareholder dynamics, among many other things. But the point of this is to provide some high level thoughts to get you started.

Steven Moe is a Partner at Parry Field Lawyers with 20 years experience and a focus on empowering impact

Steven can be contacted on:

E stevenmoe@parryfield.com

T +64 21 761 292