The Supreme Court has recently decided the case of Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited which has direct implications for company directors. What can directors learn from this case and how will it affect how directors undertake their duties? We set out the key facts and principles so that you can stay safe.

Mainzeal was a property focussed company that went into liquidation owing approximately $110 million to creditors. As the Board was chaired by a former Prime Minister it has gotten a lot of attention. There were five directors and four were held liable for breaches.

This case primarily looked at directors’ duties under sections 135 and 136 of the Companies Act 1993. These sections recognise creditors interests that are to be considered by directors where a company is insolvent or near insolvent.[1] Section 135 provides that a director must not carry on a company’s business in a manner likely to create substantial risk of loss to its creditors. Section 136 outlines the duty of a director not to agree to incurring obligations unless they reasonably believe it will be able to be performed on time.

The Court upheld the Court of Appeals finding that the directors had breached their duties under these sections and compensation was granted under s 136 for new debt incurred but not under s 135 as net deterioration to creditors was not proved.[2]

The Supreme Court summarises the implications for directors of their approach to ss 135 and 136 liability. Three key takeaways for directors from this case are:

- Don’t rely on assurances

- Get advice early

- Know your duties

1. Don’t rely on assurances

Mainzeal had been balance sheet insolvent for years yet continued to trade because its directors primarily relied on assurances of support from companies it was associated with.[3] One company provided a formal letter of support, otherwise known as a “letter of comfort”, while other assurances were less formal.[4] However, these ‘assurances’ were far from sure and critically they were not legally enforceable.

The Supreme Court stated that where assurances are not legally or practically enforceable and not honoured, relying on them will raise questions as to the reasonableness of doing so.[5] In this way it may be found that relying on such assurances is unreasonable and may result in a breach of directors’ duties which may also lead to potential liability.

Key point: Assurances should be documented and legally binding.

2. Get advice early

The Court does consider this when looking at the actions a director took. Directors should seek professional or expert advice early and from sources that are independent from the company. This can help directors be sure of their duties and how to avoid potential breaches, and in turn avoid personal liability. It means they can squarely address whether there are potential risks of loss to creditors or doubt as to whether it is reasonable to believe that obligations incurred will be able to be honoured.[6] By engaging external advice early, directors allow themselves reasonable time decide the course of action they should take.[7]

Section 138 of the Companies Act 1993 specifically allows directors to rely on such advice where they act in good faith, make proper inquiries where circumstances require it and have no knowledge that relying on the advice is unwarranted.[8] Directors should ascertain whether the relevant risks can be avoided or a plan for continued trading can be used to avoid the serious loss or creditors and meet the obligations agreed to.

Directors that do this will be appropriately considering creditors interests and it may help prevent personal liability. Furthermore, the courts take into consideration whether directors obtained advice when determining the reasonableness of a director’s actions.[9]

We help directors stay safe by understanding their duties. Check out our free guides or arrange a conversation with one of our team on the support we can provide you.

Key point: If you are wondering about getting advice, that means you probably should.

3. Know your duties

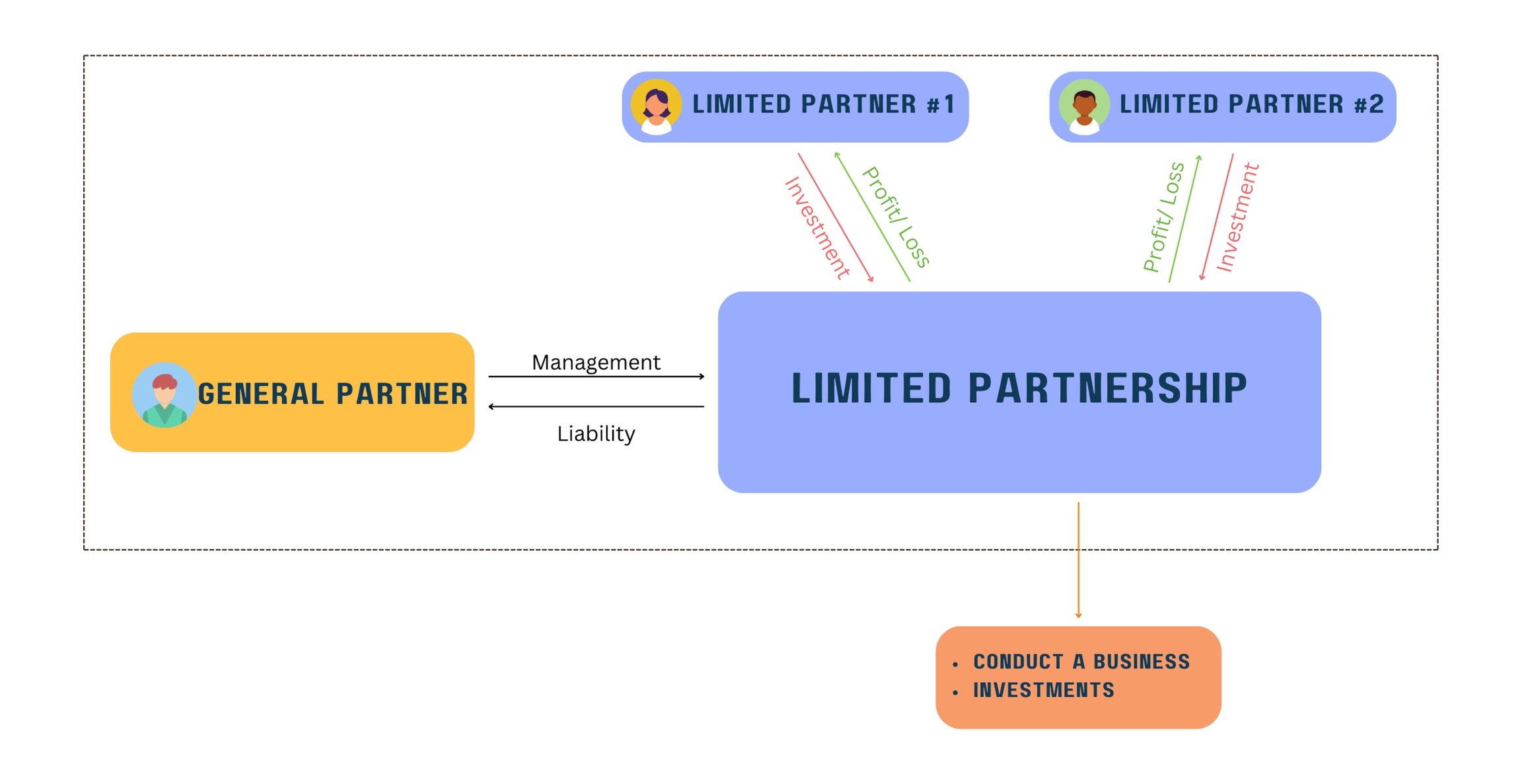

Governance is all about continual learning. While the concept of limited liability protects directors from some liability it does not protect them from their breach of duties. All the more reason for directors to know their duties and learn how to effectively discharge these duties.

This case outlines some of the duties that directors should be aware of. But they are not the only ones. Directors are required to exercise the care, diligence and skill a reasonable director would exercise in the same circumstances.[10] To do this, they need to continue to monitor the company’s performance and prospects and must not carry on trading in a way that creates a likelihood of substantial risk of loss to the company’s creditors.

[11] This is objectively assessed and directors are at fault if they allow the company to keep trading when they recognised this risk or where they would have recognised it if they had acted reasonably and diligently.[12] Further, directors should not take on new obligations without measures in place to ensure they will be met or without the belief on reasonable grounds that they will be honoured.[13]

If you are a director it is vital to ensure you know what duties who owe to the company, shareholders and creditors in order to avoid breaching them and finding yourself personally liable for it.

Key point: Keep learning individually and as a board about your duties.

Mainzeal will be talked about for a long time to come and it perhaps signals that there is a broader need for reform of the Companies Act. In the meantime there are some practical steps which you can take as a director to ensure you keep on the straight and narrow and avoid liability if you are involved in governance of a company which is getting close to insolvency.

—

If you have any further queries please do not hesitate to contact one of our experts at Parry Field Lawyers.

This article is general in nature and is not a substitute for legal advice. You should talk to a lawyer about your specific situation. Reproduction is permitted with prior approval and credit being given back to the source.

—

[1] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) [2023] NZSC 113 at [359].

[2] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [371]-[375].

[3] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [2].

[4] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [36]-[37] and [42].

[5] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [363].

[6] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [270].

[7] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [271].

[8] Companies Act 1993, s 138(2).

[9] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [273].

[10] Companies Act 1993, s 137.

[11] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [270] and [360].

[12] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [360].

[13] Yan v Mainzeal Property and Construction Limited (in Liq) at [273] and [369].